From Feedback Loops to Self-Regulating AI: How the Pioneers of Cybernetics Shaped Modern Machine Learning

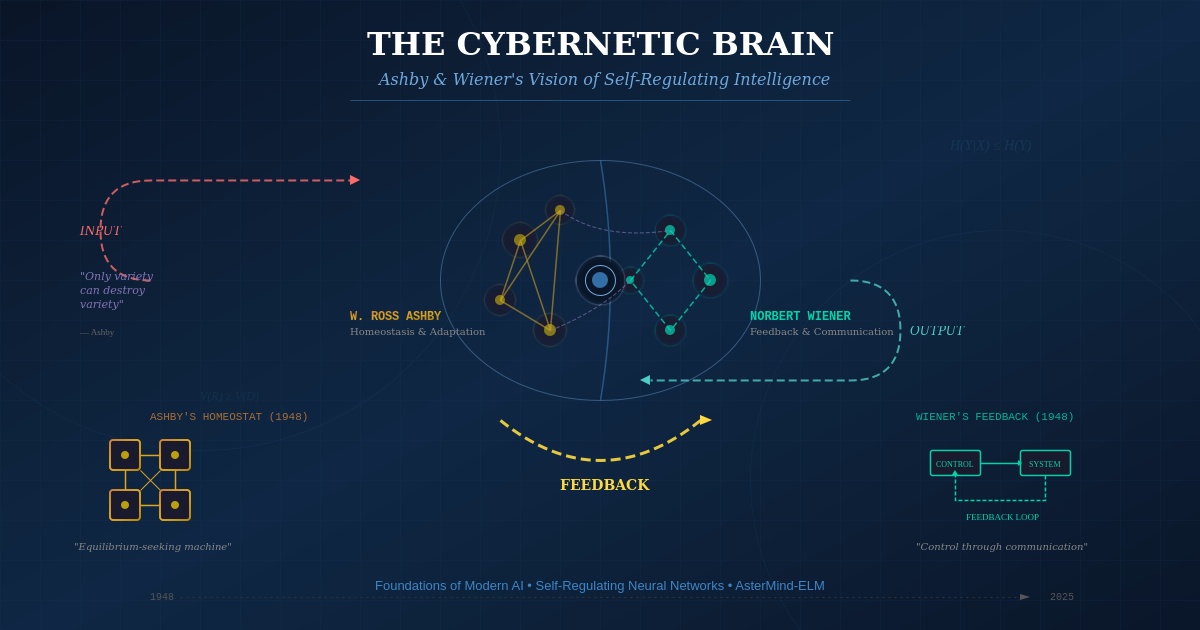

The visionary work of W. Ross Ashby and Norbert Wiener in the 1940s laid the foundation for today's most advanced AI systems—including the self-regulating neural architectures powering AsterMind-ELM.

Introduction: The Forgotten Fathers of Artificial Intelligence

When we discuss the history of artificial intelligence, names like Alan Turing, John McCarthy, and Marvin Minsky often dominate the conversation. Yet decades before "artificial intelligence" became a formal discipline, two remarkable scientists were already building the theoretical and practical foundations for machines that could learn, adapt, and regulate themselves.

Norbert Wiener (1894–1964) and W. Ross Ashby (1903–1972) were the architects of cybernetics—a revolutionary field that unified the study of control, communication, and feedback in both living organisms and machines. Their insights, developed in the crucible of World War II and its aftermath, are experiencing a remarkable renaissance in modern AI systems.

At AsterMind, we've built our Intelligent Adaptive Engine technology on principles that would be immediately recognizable to Wiener and Ashby. Our self-regulating neural architectures, homeostatic feedback control, and adaptive learning systems are direct descendants of cybernetic theory. This article explores how these visionary ideas from the mid-20th century are now powering the next generation of browser-native, privacy-preserving AI.

Part I: Norbert Wiener and the Birth of Cybernetics

The Mathematician Who Saw Feedback Everywhere

Norbert Wiener was a child prodigy who earned his PhD from Harvard at the age of 18. By the time World War II arrived, he had established himself as one of the world's leading mathematicians at MIT. But it was the war itself that would catalyze his greatest contribution to science.

Tasked with developing automated anti-aircraft systems, Wiener confronted a problem that seemed intractable: how could a machine track and predict the erratic movements of an enemy aircraft? The answer, he realized, lay not in brute-force calculation, but in feedback loops.

Traditional machines of the era followed fixed, pre-determined sequences of operations. Wiener's insight was profound: machines could operate dynamically, responding to and adapting based on incoming data. The anti-aircraft system he envisioned would continuously adjust its aim based on the observed effect of its previous adjustments—a self-correcting mechanism that mirrored how living organisms maintain stability.

Cybernetics: Control and Communication

In 1948, Wiener published his landmark book, Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine. The title itself was revolutionary—it asserted that the same mathematical principles governed both biological and mechanical systems.

Wiener derived the term "cybernetics" from the Greek word κυβερνήτης (kybernḗtēs), meaning "steersman" or "governor." The metaphor was apt: in steering a ship, the position of the rudder is adjusted in continual response to the effect it is observed as having, forming a feedback loop through which a steady course can be maintained in a changing environment.

At the core of Wiener's theory was the message (information), sent and responded to (feedback). He argued that the functionality of any system—whether a machine, an organism, or a society—depends on the quality of these messages. Information corrupted by noise prevents homeostasis, the equilibrium state that all self-regulating systems strive to maintain.

The Prophet of Machine Intelligence

Wiener was among the first to propose that all intelligent behavior is the result of feedback mechanisms that could be simulated by machines. This was an important early step in the development of what we now call artificial intelligence. In Cybernetics, he even speculated about chess-playing machines, predicting they could "very well be as good a player as the vast majority of the human race." He was right—though it took until 1996 for IBM's Deep Blue to defeat world chess champion Garry Kasparov.

Yet Wiener was also deeply troubled about the implications of technology on society. In The Human Use of Human Beings (1950), he warned against machines being used to control humans and displace jobs. He advocated for technology that enhances human abilities rather than controls them—a philosophy that remains urgently relevant in the age of AI.

Part II: W. Ross Ashby and the Design of Adaptive Systems

The Psychiatrist Who Built a Brain

While Wiener approached cybernetics from mathematics and engineering, W. Ross Ashby came from medicine and psychiatry. Working at mental hospitals in England, Ashby became fascinated by a fundamental question: how does the brain adapt to maintain stability in an ever-changing environment?

Ashby was, in the words of his contemporaries, "the major theoretician of cybernetics after Wiener." His two books—Design for a Brain (1952) and An Introduction to Cybernetics (1956)—introduced exact and logical thinking into the young discipline and remained influential for decades.

The Homeostat: A Machine That Seeks Equilibrium

In 1948, the same year Wiener published Cybernetics, Ashby built a remarkable machine called the Homeostat. This device demonstrated something extraordinary: a simple mechanical process could return to equilibrium states after disturbances at its input.

The Homeostat consisted of four interconnected units, each affecting the others through feedback loops. When disturbed, the machine would search—seemingly randomly—for a stable configuration. Wiener himself called it "one of the great philosophical contributions of the present day."

What made the Homeostat revolutionary was that it didn't follow a predetermined program. Instead, it explored its possibility space until it found stability. This was adaptive behavior emerging from mechanism—a proof of concept that machines could exhibit properties previously thought unique to living organisms.

Alan Turing was so intrigued by Ashby's work that he wrote to him in 1946, suggesting Ashby use Turing's Automatic Computing Engine (ACE) for his experiments. The intersection of these two giants—one focused on computation, the other on adaptation—foreshadowed decades of development in machine learning.

The Law of Requisite Variety

Perhaps Ashby's most enduring contribution is his Law of Requisite Variety, which he articulated in An Introduction to Cybernetics. Stated simply: "Only variety can destroy variety." Or, as it's often paraphrased: "Only complexity absorbs complexity."

What does this mean in practice? A regulator (whether a thermostat, an immune system, or an AI) must have at least as much variety in its responses as there is variety in the disturbances it faces. An air conditioner with only one setting cannot maintain comfortable temperature across seasons. A chess program with only one strategy cannot defeat skilled opponents.

Ashby and his colleague Roger Conant extended this into the Good Regulator Theorem: "Every good regulator of a system must be a model of that system." For an AI to effectively respond to a complex environment, it must contain within itself a representation of that environment's essential dynamics.

These insights have profound implications for modern AI design. They suggest that effective artificial intelligence isn't about raw computational power—it's about matching the complexity of the model to the complexity of the problem.

Part III: Cybernetics Meets Modern Machine Learning

The Principles That Never Went Away

Although the term "cybernetics" fell out of fashion in American academia (partly because John McCarthy deliberately coined "artificial intelligence" to distance his work from Wiener's), the core ideas never disappeared. They simply migrated into other disciplines and reemerged under different names:

- Control theory in engineering

- Systems theory in management and biology

- Reinforcement learning in AI

- Adaptive systems in robotics

- Homeostatic networks in computational neuroscience

Today, we're witnessing what the journal Nature Machine Intelligence calls a "return of cybernetics." As AI systems become more complex and autonomous, the foundational questions Wiener and Ashby asked—about feedback, adaptation, stability, and regulation—have become unavoidable.

Where Traditional Neural Networks Fall Short

Modern deep learning has achieved remarkable successes, but it struggles with exactly the problems cybernetics was designed to address:

| Challenge | Traditional Deep Learning | Cybernetic Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Adaptation | Requires retraining on new data | Continuous self-adjustment |

| Stability | Can drift or catastrophically forget | Homeostatic regulation |

| Feedback | Limited to backpropagation | Rich, multi-level feedback loops |

| Efficiency | Massive compute requirements | Minimal, closed-form solutions |

| Explainability | "Black box" decisions | Observable regulatory mechanisms |

The neural networks that dominate AI today—trained via gradient descent over millions of iterations—would have seemed almost paradoxically inefficient to Ashby. His Homeostat achieved adaptation without any training algorithm at all. It simply explored until it found stability.

Part IV: AsterMind-ELM—Cybernetics Reborn in JavaScript

Extreme Learning Machines: Ashby's Vision in Code

At AsterMind, we've built our technology on a neural network architecture that would have delighted both Wiener and Ashby: the Extreme Learning Machine (ELM).

Developed by Guang-Bin Huang in 2006, ELM represents a return to cybernetic first principles. Unlike traditional neural networks that laboriously tune all their weights through iterative backpropagation, ELM takes a radically different approach:

- Random hidden layer: The connections between input and hidden neurons are randomly assigned and never updated

- Closed-form solution: Only the output weights are computed—and they're calculated analytically in a single step

- Instant training: What takes traditional networks hours or days happens in milliseconds

This architecture echoes Ashby's Homeostat, which also used random exploration to find stable configurations. The insight is the same: you don't need to optimize everything. You need to find the right structure that allows rapid, stable adaptation.

AsterMind-ELM: Browser-Native Cybernetic Intelligence

We've taken ELM and rewritten it from the ground up in pure JavaScript—not a Python library with a JavaScript wrapper, but native code designed for the browser and Node.js environments. This enables something Wiener and Ashby could only dream of: intelligent systems that run entirely on-device, with complete privacy, at millisecond speeds.

Core Cybernetic Features in AsterMind-ELM:

| Feature | Cybernetic Principle | Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Millisecond Training | Efficiency of closed-form solutions | Moore-Penrose pseudoinverse |

| On-Device Processing | Local feedback loops | Browser/Node.js native |

| Model Chaining | Hierarchical regulation | Connect ELMs like LEGO blocks |

| Transfer Entropy Metrics | Information flow measurement | Built-in explainability |

| Deterministic Math | Reproducible regulation | No stochastic gradients |

AsterMind-ELM Premium: Self-Regulating AI Architecture

Our Intelligent Adaptive Engine, takes cybernetic principles to their logical conclusion. We've built what we call a "cybernetic organism for continual learning"—a self-regulating AI architecture with:

Homeostatic Feedback Control Just as Ashby's Homeostat sought equilibrium after disturbances, The Intelligent Adaptive Engine continuously monitors its own performance and adjusts its internal parameters to maintain optimal operation. When the data distribution shifts, when user behavior changes, when the world evolves—the system adapts.

Novelty Detection Inspired by Ashby's Law of Requisite Variety, our system recognizes when it encounters situations outside its training distribution. Rather than confidently producing wrong answers (a failure mode of many AI systems), The Intelligent Adaptive Engine flags uncertainty and can request human guidance.

Online Learning Traditional AI systems are frozen after training—they can't incorporate new information without expensive retraining. The Intelligent Adaptive Engine learns continuously, updating its models in real-time as new data arrives. This is the adaptive, feedback-driven learning that Wiener envisioned.

Symbolic Control Interfaces Wiener warned about the dangers of autonomous systems that humans couldn't understand or control. The Intelligent Adaptive Engine maintains human-in-the-loop capabilities through symbolic interfaces that make its decision-making transparent and steerable.

Drift Detection and Self-Healing Our AsterMind Resiliency Sidecar (ARS) embodies the cybernetic principle of error-correcting feedback. It monitors for schema drift, UI changes, and data anomalies, automatically re-mapping and adapting to maintain stable operation—just as a biological organism maintains homeostasis despite environmental changes.

Part V: Practical Applications—Cybernetics in Action

Cybernetic DataOps Suite: Adaptive Data Operations

Ashby's Good Regulator Theorem states that every good regulator must be a model of the system it regulates. Our AsterMind Cybernetic DataOps Suite applies this principle to living data systems through four integrated modules: SchemaSense™, Normalize™, DriftGuard™, and Data Reflex™.

When data schemas change—as they inevitably do—traditional systems break. The Cybernetic DataOps Suite maintains internal models of data relationships and automatically adapts when it detects drift. It's not following a fixed mapping; it's regulating a complex data flow using cybernetic feedback, continuously observing, adapting, and responding as data evolves.

RAG Solution: Information Flow Optimization

Wiener's core insight was that the functionality of any system depends on the quality of messages flowing through it. Our AsterMind Cybernetic Chatbot (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) solution applies this to document intelligence.

Using Transfer Entropy—a mathematical measure of information flow that Wiener would have recognized—we optimize how information moves from retrieval to reranking to summarization. The result is a system that maintains coherence and relevance through explicit feedback mechanisms, not just statistical correlation.

Synth: Privacy Through Cybernetic Generation

Wiener was deeply concerned about privacy and the control of personal information. Our AsterMind Synth generates synthetic data that preserves the statistical properties of original datasets while eliminating privacy risks.

This is cybernetic regulation applied to data: the synthetic generator maintains feedback with the original data's distribution, ensuring the output remains useful while the personally identifying signals are filtered out—like noise removed from a communication channel.

Part VI: The Future—What Wiener and Ashby Would Build Today

Beyond Backpropagation

The dominance of gradient-based deep learning is showing cracks. Training costs are astronomical. Carbon footprints are enormous. Models are opaque, brittle, and prone to hallucination. The AI community is increasingly looking for alternatives.

Cybernetics offers a different path: systems that achieve intelligence through structure and feedback rather than brute-force optimization. ELM-based architectures like AsterMind demonstrate that you don't need billions of parameters and thousands of GPU-hours to build useful AI.

The Edge AI Revolution

Wiener imagined feedback systems that operated in real-time, in the field, in direct contact with the environment they regulated. Today's cloud-based AI—with its latency, privacy concerns, and infrastructure costs—would have seemed like a step backward.

AsterMind's browser-native architecture realizes Wiener's vision: intelligence that runs where it's needed, processes data where it's generated, and maintains privacy by never transmitting sensitive information. This is cybernetics for the edge computing era.

Human-Machine Symbiosis

Both Wiener and Ashby were concerned with the relationship between humans and machines. They didn't want to build autonomous robots; they wanted to build tools that enhanced human capabilities.

AsterMind's human-in-the-loop features—the symbolic interfaces, the explainability metrics, the uncertainty flags—embody this philosophy. Our AI doesn't replace human judgment; it amplifies it. When the system is uncertain, it asks. When decisions matter, humans remain in control.

Conclusion: Standing on the Shoulders of Cybernetic Giants

Seventy-five years after Wiener coined the term "cybernetics" and Ashby built his Homeostat, their ideas are more relevant than ever. The principles they discovered—feedback, adaptation, homeostasis, requisite variety—aren't just historical curiosities. They're engineering tools for building AI systems that actually work in the real world.

At AsterMind, we've built our technology on these foundations. Our Extreme Learning Machines achieve in milliseconds what gradient descent achieves in hours. Our self-regulating architectures maintain stability in changing environments. Our feedback-driven systems adapt without retraining, explain their reasoning without external tools, and run entirely on-device without cloud dependencies.

Wiener wrote that "the first industrial revolution was the devaluation of the human arm by the competition of machinery... The modern industrial revolution is similarly bound to devalue the human brain." But he also showed a different path—machines that work with humans, that enhance rather than replace, that provide feedback rather than control.

That's the path we're walking at AsterMind. And we're grateful to stand on the shoulders of these cybernetic giants who lit the way.

Learn More

Explore AsterMind's Cybernetic AI Technology:

- AsterMind-ELM Community Edition — Free, open-source Extreme Learning Machine library

- AsterMind-ELM Premium — Self-regulating AI with homeostatic feedback control

Further Reading on Cybernetics:

- Wiener, N. (1948). Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine

- Ashby, W.R. (1956). An Introduction to Cybernetics — Available free online

- The W. Ross Ashby Digital Archive — ashby.info

This article is part of the AsterMind Learning Center series exploring the theoretical foundations of modern AI.